Flight into the unknown in SoCal (Southern California Tango Championship & Festival). My first tango festival, my first competition, my first time in California, USA. I’d never competed in tango. I hadn’t even been dancing for a year. But something inside me told me I had to go. That this experience had something in store for me.

Yes, I competed. I dared. But I did so out of ignorance. I apologize—to the judges, the teachers, my classmates—because I didn’t know what I was doing… at least not until I arrived in SoCal.

It all started two weeks earlier. Wook, a Korean guy I’d danced a couple of tandas with in Sarasota, wrote me on Facebook: “Do you want to compete with me at a festival in the Amateur Floor Tango category?”

I, who understood “amateur” as “beginner,” said yes almost without thinking. There were only two days left to register. While I tried to get tickets, he took care of everything else.

After buying the ticket, I started asking around. I wrote to Guada and Junior Cervilla, two of the best tango dancers I know, who organize a milonga once a month in Sarasota, which was my first milonga (which, by the way, I attended for the first time after only three classes… I’m ashamed to admit it).

Guada replied: “The level there is high. It’s not like here. Those who are going to the World Cup go. But enjoy it, it’s going to be a great experience. You’ll like it.”

And that’s when I realized that, once again, I had jumped out of the plane without asking if there was a parachute. But as I always say: my greatest fear is over, and I have little to no fear of ridicule.

During those two weeks before the festival, I was only able to dance with my partner about five more times. Wook had suggested I dance with him because his wife’s mother had gotten sick, and now she had to take care of her and couldn’t travel. Wook decided to look for someone to compete with in the amateur tango category. I suppose he wrote to several people beforehand, but he just happened upon me—the one who said yes without much hesitation.

During our conversation, he explained his family situation to me and also said something that touched me deeply: “I’m almost 55 years old, this could be my first and maybe my last chance to compete.”

That convinced me. There was nothing more to say. I bought the tickets and set off on the adventure.

Days before the festival, Wook fell ill. We weren’t able to practice as much as we would have liked, and yet, against all odds, we made it to the semifinals. But I knew—I felt it—that the judges could see when there was no connection with your dance partner. There was a lack of communication and synchronicity. After the California Tango Festival, I took the time to listen to my partner more closely. We came from completely different worlds.

In the eyes of the experts, he sacrificed the embrace for the sake of the move. But for him, that close embrace, which seemed warm and necessary to me, was in itself an enormous act of disrespect toward his wife. A cultural sacrifice. And how can I explain tango to him? They are words he doesn’t understand, foreign sounds, a completely different phonetic.

He writes in figures that are indecipherable to me, and I’m no different to him. If it weren’t for English, we wouldn’t be able to hold a conversation. And when he speaks in his own language, it sounds strange and inharmonious to my ear.

Even so, we made it far. And we’re proud. We’re probably not cut out to dance tango together, but I’m truly grateful to you for inviting me to this madness. It was, without a doubt, one of the most enriching experiences of my life. Tango, though fragile, built a bridge between two worlds.

Crossing to the other side

To get to the event, you had to cross a path that connected the two hotels: my standard one—comfortable, yes, but unpretentious—and the Hilton where the SoCal Tango Festival California was being held. As I walked toward it, the atmosphere began to transform. The path was beautiful, almost ceremonial. You felt like you were entering another world: more elegant, more vibrant, more alive.

As soon as I set foot inside the Hilton, I felt it. Everything was different. In the background, a sign announced the Tango California festival. I had to walk a few more steps, turn right, then left… and there it was: the heart of the event.

The registration tables. There they handed out bracelets, sold individual tickets for classes or milongas, and you could feel the energy of those who had made all this possible. It was there that I met Dionisio, the cameraman. As usual, a little lost, I looked at him, not knowing where to go. Without hesitation, he asked me if I needed help. I told him yes, that I had just arrived. “Are you coming for the festival?” he asked. When I said yes, he smiled at me with a very special warmth: “I’ll take you.” He walked me to the table, and finally, I received my bracelet.

I’d made sure to buy the full ticket. I wanted to experience it all. I didn’t come to see what was happening. I came to be involved in everything.

That first day, after settling in, I went shopping with my partner. We went to a Korean supermarket—a very special experience because he’s Korean too—and I discovered completely new flavors, textures, and smells. It was, oddly, the only thing I saw of Irvine, because outside of the festival, I didn’t explore anything else. I just came to the event. It was my first time in California, my first time at a tango festival, my first time in a competition… and also, my first year dancing tango! Everything was a first.

My first class was with Manuela Rossi and Juan Malizia, stage tango specialists. They’re brilliant. I took two classes with them that day. I was lost, of course, not knowing what to do next or where to go. During one of those breaks, my partner had to go compete, leaving me alone in one of the rooms… That’s when Clarisa Aragón arrived.

I took a class just for followers, for girls. I loved it. Although I often had to do the exercises alone because there weren’t enough of us to pair up, I thoroughly enjoyed it. In that class, I also met Chris, part of the staff. He noticed me, we connected. I think my dedication caught his attention. From then on, we started talking. It was lovely. I began to form real bonds with people who, until then, had been complete strangers.

Clarissa’s class was special. She’s an angel, a sweetness… a way of teaching that envelops you.

That night, I supported my partner, Wook, and also Andrés Bravo and Carolina Balmaseda, who I already knew would be competing. My heart has been with them for a long time; I admire them. But my heart also went out to Jael Mantilla and Jesús Aranguren, two guys I had met just eight days before the event because Wook had hired them for two hours to help us prepare for the competition… and I ended up sharing a room with Jael. I experienced the festival from many angles: as an apprentice, as a naive competitor, as a friend of a professional who lived it all with passion.

What I didn’t know was that this trip would mark a before and after, not only in my dance, but in my way of inhabiting art…

Competing without connection (cultural or musical)

How did I survive an amateur tango competition with a Korean partner who didn’t speak a common language?

We barely knew each other; we didn’t speak the same language. We had different musical backgrounds, different body styles. And yet… We made it to the semifinals. Against all odds.

My mind began writing this from the moment I arrived at the event. I’m aware that, at some point, or perhaps there’s already a meme circulating about my reaction when, leaving our hair on the fence (as we say in my country), my partner and I made it to the semifinals. I couldn’t believe it… That’s me while I was dancing and experiencing the festival, writing chapters, paragraphs, and even pages of stories, reflections, and questions to myself, which I then answered. And not just in tango; this is, if you haven’t noticed yet, deeper than a simple description of the festival.

I thought about my dad, about my life, about how our egos play tricks on us, even if only for a few seconds, and we don’t realize how hurt we are. I felt and reflected on how imperfect I am. During a class, on the day of the semifinal, I got frustrated with Wook during the musicality class, taught by Clarisa Aragón and Jonathan Saavedra. Since we both heard music so differently, we clashed. Minutes after the class ended, Clarisa, with that charisma and special gaze, approached him and explained something. It was just the moment we had to leave. I left the room and boom! My knee hurt, not the one that always hurts, but the one that’s supposed to be better. In the midst of that frustration, not knowing how to communicate with my partner harmoniously and as a team, I stopped outside the room—the same one where we would dance later—drank some water, and asked myself: Why does my knee hurt? And the answer was clear: that’s ego, Sara. We have to subdue our ego and understand that we’re different. Maybe, in the midst of my reflections, my faces were funny, but I had moments when I seemed to be staring into space when in reality I was writing in my mind, capturing inspiration, and photographing images that are now translated into words.

To summarize that reflection: my knee, as if by magic, stopped hurting. Maybe my ego kicked in. Did I want to leave my partner and not show up with him because it wasn’t what I wanted? Fortunately, I reflected, apologized, and we moved on.

That’s how I began to understand how the body and music combine and become art. But on the night of the semifinal, the same night we obviously didn’t make it to the final, my ego once again told me, “Why not?” But I had to say, “You’re not up to it.” There are no improvised partnerships here. That’s how tango works: if there’s no communication and connection with your partner—you’re not on the same wavelength—the message isn’t transmitted clearly. And that was obvious between my partner and me, so the surprise of not making it to the next round wasn’t so great.

What I understood at that moment was that connecting in tango isn’t just about synchronizing with the music, but also with your partner. Sometimes I managed to sync with my leader’s musicality, either because I understood the instruments he was following or because he, being more experienced, adjusted his cue to make me feel right. But often, despite being perfectly synchronized with the music, something was missing—a missing tango.

Sometimes the heart wants to dance, but the body doesn’t respond. It was a lesson in humility. Art isn’t always perfect, but it’s always honest.

When art speaks to you in your language, the only thing you can do… is listen

I understood what can’t be explained. Everyone says that love and art can’t be explained, they can only be felt. But how can you explain the love of art? What a more abstract thing… I can still hear the tango in my head: the violin, the piano, all mixed together.

When I heard Vanesa Villalba and Facundo Piñero speak, it was like a caress to my soul… I cried the whole class. I understood that when genius combines with perseverance, constant study, and the search not only to understand, apply, but also to explain, transmit, and communicate, wow, magic happens.

My head exploded. There’s a colloquial term in English to explain what I felt: “blowing my mind.” I never understood that expression exactly until I took the two classes with Facundo and Vanesa. In fact, I was supposed to take just one class with them and then go to class with Cynthia Palacios and Sebastián Bolivar because, like a true newbie, I wanted to try everything, see them all. But my heart was hooked right there with them.

It was as if they spoke my language, as if every word that came out of my mind traveled to their mouths and came back in a coded and clear way, as if my heart and brain flashed waves, lights, and they were able to encode it and then explain it to me in a human way in the simple language of words, also in the two languages that I speak and in the order in which I learned to speak them.

But the process was even more complex because it wasn’t just verbal language, each movement spoke, I have always said that when one dances the feet sing, they communicate with each other as if one speaks and the other responds, that was how their movements were, four lower limbs showing movements that did not come from there, they came from each cell, each joint, each part of those two masters communicated magic, greatness, simplicity, skill but above all a lot of cleanliness… Attention to detail, to simplicity.

I was sitting on the floor, like many others, looking down. It was a science and biomechanics lesson explained in poetry. The result for me? Tears of emotion. Like someone looking at a painting that moves them or listening to a song that touches their soul.

Who says art isn’t scientific? These people apply pure physics… and transform it into art.

In the end, I told Andrés Bravo, “I’d pay for all the private schools I could. I found my teachers.” And we laughed.

Vanesa and Facundo are a mix between a prodigy and a diligent student, a hybrid between Mozart and Beethoven, and me, a first-time student who can only thank life for putting me there.

I’ve cried, I’ve danced, I’ve doubted. But I’ve also understood something profound: art is home when it feels like your own.

An unexpected (and deeply Colombian) hug

Reflections from a milonga in Irvine. When body and soul sync in an embrace.

I have been very fortunate during my first year, because I live in a city where Guada and Junior Cervila are just minutes away and I can enjoy their milonga every month.

Also, Anna Critchfield, a Russian tango lover, brings in tango teachers to teach workshops whenever she can, and it was thanks to her that I was able to dance with “Dios,” as I called him, annoying Claudio Villagra. I danced a tanda with that great man and was left speechless. That was just a few days before the festival; he’s a very down-to-earth person, and so, after arriving from SoCal, I thought that maybe someone as great as him could help me understand a little of what I’d experienced, so I wrote him the following:

“I’m very sensitive today… I’ve tried to write and describe all of this in a kind of personal chronicle for catharsis (I’m a journalist). The point is that, at that festival, I danced with someone with whom I understood what connection in tango is. And since then, I’ve been asking myself: does that start happening more often once you’ve experienced it? Or is it something that only happens once every thousand years?”

In the middle of a milonga, a Colombian dancer invited me to dance. I didn’t know him. But when he hugged me—that’s what they call the position where two people connect to dance—I felt a familiar connection, like when someone speaks to you in your language. It wasn’t like dancing with a great person, like you, who left me speechless with his technique and presence. It was different. It was as if I had danced with my other self. With someone who hears and interprets music the same way I do. As if my ears and my mind were moving our bodies.

But the strangest and most beautiful thing was the energy in my chest. I felt as if I had a switched-off flashlight inside my chest, and when I started dancing, it turned on. It was a warm light, an emotion that originated in the center of my chest and descended to the pit of my stomach. The flashlight remained lit even after we stopped dancing.

I was left with that burning sensation, unable to understand how someone could hear and move almost exactly the way I would, interpreting every sound. It was like finding my tango soulmate. I understood the importance of the embrace.

I told that Colombian that I felt as if we listened to music in the same way, paying attention to the same instruments, at the same moments. I don’t know how to describe it, but I do know what I felt, and that… I’d never felt before.

He smiled and said, “That’s called connection.” And it was as if another piece of the puzzle fell into place. I understood what people mean when they talk about connection in tango. But since I’m still new to tango, I was left wondering: How often does that kind of connection happen? Will it happen again with someone else? Is it always mutual?

Villagra’s response was an audio recording because he was driving to the class he and his wife teach on Tuesdays in Miami, and in the recording he told me: “That’s so nice. It’s not that common, much less mutual, but that’s tango. Try not to lose that connection, especially if it’s mutual.”

Sometimes it’s better not to know:

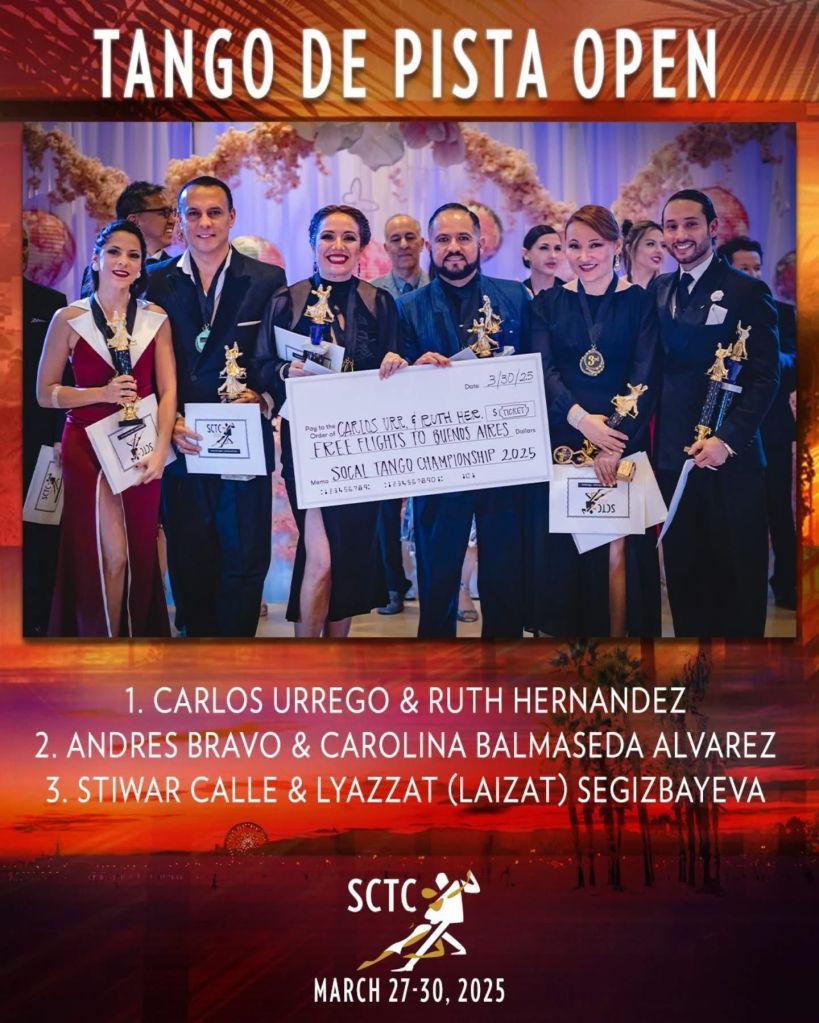

And the next day, the Colombian with whom I shared three unforgettable sessions won first place in the Tango de Pista and Milonga categories, and second place in the Waltz with his partner. I felt so happy for them. Honestly, the day of the final was the first time I even noticed him and his partner as competitors, because my heart was with two other couples: Carolina Balmaseda and Andrés Bravo, Jael Mantilla and Jesús Aranguren. Not only do I appreciate them, I also think they’re incredibly good.

That day, although my heart was still with Caro and Andrés, I decided to open my eyes and observe my surroundings, to be a little more objective. It was then that I saw the greatness of Carlos Urrego and Ruth Hernandez. I felt that magic again… as if their feet were producing the sounds my ears most cherish. I danced with them, seated, with my eyes, with my soul. But I also had the responsibility to record my friends and support them. It was a battle of titans. Caro and Andrés have a stage presence that can’t be ignored. I think they were born to dance together. I saw them do it for the first time when they had barely decided to join together as a couple. Without rehearsals or anything else, they were already one. They were already a spectacle.

That night, Carlos won. And I was happy, because Caro and Andrés also won in the stage category, with a display of technique, feeling, and cleanliness that only they can achieve.

Carlos asked me to dance again, but now I knew who he was. He had already become a champion. And yet, he danced with me again. From the moment we stood facing each other, without touching, before the hug… puff… it happened again: a single pair of ears with four legs to interpret the sound.

I wonder if it will happen again. Because it was magical.

Sometimes tango doesn’t require technique. Just presence and a heart willing to beat in time.

Is it technical? Is it chemical? Is it cultural? Connection is the mystery that haunts us and sustains us in every round.

And perhaps, like art, it can’t be explained. It’s felt. Or not felt. And that’s okay too.

In the end, I think the real connection was with myself. I became a child again. I think the real connection was with the 4-year-old Sara who danced all day, the one who only wanted to go to her folkloric dance and music classes. I don’t know how I managed to silence her for almost 15 years. I filled myself with excuses after an accident that left me with a bruised knee. That, combined with my adult responsibilities, extinguished my inner child, the little girl whose passion was dancing.

Milonga Nights: Art as an Emotional Mirror.

At the end of each day, there was a milonga, it was like a trip back in time. The music, the DJs, the performances… everything was magical. Not just the music, but also the people, the elegance on the dance floor. The atmosphere was incredible. When Sebas and Cynthia danced their tribute to the milonguero “Parejita,” who had just passed away at 95, my skin crawled and, for a change, my eyes watered.

All the performances were top-notch. Facundo and Vanesa’s show was a masterpiece, and Juan Malizia and Manuela Rossi’s dancing was hypnotic. It wasn’t just watching them dance; it was seeing art in motion. And on the final night, when all the maestros danced together, I felt a unique connection with every movement.

This was my first festival, and while I don’t have the authority to compare it to others, I can say with certainty that the SoCal Tango Festival changes lives. It’s a transformative experience. It’s worth every penny.

The Beauty That Hurts: Back Home:

The day I returned, the sky was gray, the emptiness felt empty… everything felt like a farewell. I walked with nostalgia, as if I were no longer in that magical world of tango.

However, at the hotel restaurant, I found a familiar face who invited me to join her and her friend for breakfast. She didn’t remember my name, but neither did I remember hers. Embarrassed, when she asked me my name again, she said, “Sorry, I’m just getting old and have dementia.” I smiled and said, “I don’t remember yours either.” The three of us re-introduced ourselves. Susan kept repeating that she had dementia, and her friend Thai, a little annoyed, told her, “It’s not true, don’t say that.” In my ignorance, as bold as ever, I began to explain to Susan why she shouldn’t keep telling herself that she has dementia, and I told her that her brain would eventually believe it.

It was a lovely breakfast because I love reading, and we ended up talking about brain functions. To my surprise, Thao is a neurologist and Susan Aree is a dentist. Thao Nguyen, the neurologist (I didn’t know their professions yet), looked at me and said exactly what you’re saying, and gave us a lecture on how our brain programs itself. She calls it self-fulfilling prophecies, meaning your brain ends up making what you keep saying come true. It was, without a doubt, the best breakfast and the best way to end my trip to the hotel where, in a way, I had had many epiphany moments.

On my first flight back, I arrived with very little time for my connection, tired because I’d been writing parts of this chronicle on the plane, some in my head and others on my phone. I ran a marathon for nothing, since the second flight was delayed. I went to the bathroom and, for a change, wrote more lines in my head about my emotional experience at the SoCal Tango Festival. When I landed, I realized I was walking in the wrong direction, away from the gate. I stopped dead in my tracks (another meme for anyone who noticed), turned around, and laughed to myself until I sat on the floor to wait for my flight.

In Phoenix, I was fortunate enough to meet Zilfe Fever, who, like me, had traveled from Sarasota to SoCal and shared many of my emotions. I felt the festival left me with something profound, something I’m still processing.

I wasn’t prepared for tango to confront me with so much. I felt vulnerable, exposed, human.

Art that connects isn’t always comforting. Sometimes, it only shows you what you still need to look at. And so it was. When I got home, with a mild case of the flu that I know my body had somatized, I felt like I’d left a part of myself behind, but I’d also taken with me a piece of everything I’d experienced. And as I continue to process this experience, I wonder if everything I felt at the festival, that unique connection, will ever be repeated. But for now, all I know is that it was an experience I’ll never forget.

This is how this Epiphany in heels ends.

Photos by SoCal 2025 and Don An.